Why utilization review’s middle child is undervalued but deserves more innovative tech now

We’ve all heard about prior authorization, but what is concurrent authorization? What are concurrent reviews?

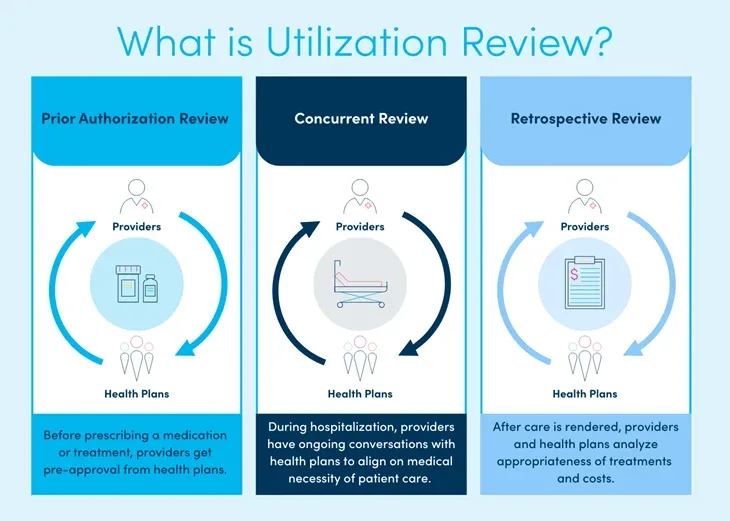

All three of the processes below make up utilization review.

Utilization review ensures the collection of information at the initial point of entry and during treatment in a patient’s care to evaluate medical necessity and the appropriateness of care related to desired outcomes. (Source)

Utilization Review’s Three Phases:

- Prior authorization review, sometimes known as pre- or prospective-authorization review, occurs prior to the administration of treatment. These reviews ensure the requested care is medically appropriate.

- Concurrent review is a utilization review process that occurs while a patient is actively receiving treatment, such as during a hospital stay. It evaluates the medical necessity and appropriateness of ongoing healthcare services to ensure the patient is receiving the right level of care, at the right time, in the right setting. Concurrent reviews support efficient, cost-effective treatment by assessing whether continued care remains justified. They can also involve care coordination across multidisciplinary teams, disease management, discharge planning, and transitions to other care facilities. This process helps prevent unnecessary or prolonged care, improve patient outcomes, and manage healthcare costs.

- Retrospective review occurs after treatment has been administered to evaluate the success of the provided care and determine if the billed codes are correct. Additionally, through retrospective reviews, utilization management guidelines are regularly updated based on treatment efficacy. Future requests for these treatments are then more likely to be approved based on previous successes. This review process is especially important as new treatments and medications enter the market.

It should be noted that phases two and three — concurrent and retrospective reviews — are behind the scenes. Most patients are likely unaware that these processes are occurring during or after their hospital stay. While concurrent and retrospective reviews may not directly impact the cost to the patient, it impacts the payment received by the hospital for the care that was provided to the patient.

Why prior authorization has been in the spotlight more:

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) prioritized fixing it. CMS established a January 2027 deadline by which impacted payers must implement a Prior Authorization API to facilitate electronic prior authorization requests and responses, with a focus on streamlining the process and improving interoperability. The rule requires impacted payers to send prior authorization decisions within 72 hours for urgent requests and seven calendar days for non-urgent requests for medical items and services.

Why did they prioritize prior authorization?

- Medicare is only concerned with prior authorizations (it is a control put in place to give providers and suppliers “some assurance of payment for items and services that receive provisional affirmation decisions” – Medicare only reviews and pays for claims submitted during this process). Thus, prior auth was prioritized because of the financial impact that it has on hospitals.

- For example, when prior auth produces a positive impact, the authorization is complete, a patient comes in for a planned procedure, and everyone gets paid (the hospital and physician or surgeon).

- When it produces a negative impact, a patient comes in and has a planned procedure. A physician or surgeon will get paid for the services they provided, however the hospital will not. In most cases where the hospital is not paid, the culprit is a technical denial, because the administrative process was not followed and/or completed. The hospital would then have to write off those fees, because the patient’s procedure was not approved prior to the patient entering the hospital. Some payers will allow reconsideration of these denied claims, but many will not.

- Breakdowns during prior authorization can lead to delays or even abandonment of recommended care. (Source)

- Even worse, prior authorization can be seen as a barrier to care and issues with prior authorization can sometimes even lead to death. “Patients are dying while they are waiting for prior authorization when it comes to their cancer.” (Source)

- Manual prior authorizations cost more money than electronic ones, and prior authorization ultimately ends up costing the healthcare system more than it saves. (Source)

We are all patients and therefore more aware of this process.

For example, before a surgery is scheduled or a prescription is refilled, patients are typically made aware of when insurance has authorized it and can even be provided with a patient balance bill estimate ahead of time.

Why concurrent review is undervalued, but needs to also be improved now:

Denials. No one is prioritizing concurrent denials, but these are very real for the hospital. For example, each denial is handled per the specific contract terms between each payer partner and the hospital – concurrent denials, Peer-to-Peers, and formal appeal processes may all call for different processes per payer – and yet many Directors of Case Management may be unaware of what comprises those contracts.

Misalignment during any of these steps can equate to a hefty price tag. Medical necessity denials are a $2.5 billion problem for healthcare organizations each year. That’s around $5 million in denials per provider, on average, each year, that is written off due to misalignment on how claims were handled, processed, and/or misinterpreted between stakeholders regarding what should be considered medically necessary treatment for the patient.

![]() Concurrent authorization benefits are less immediately visible compared to prior authorization or retrospective review, because concurrent review occurs in real-time – thus giving the misguided perception that it’s merely an administrative hurdle. On the contrary, concurrent review presents a strategic opportunity to optimize care delivery and coordination.

Concurrent authorization benefits are less immediately visible compared to prior authorization or retrospective review, because concurrent review occurs in real-time – thus giving the misguided perception that it’s merely an administrative hurdle. On the contrary, concurrent review presents a strategic opportunity to optimize care delivery and coordination.

- How expensive is this problem? Avoidable delays in care make up roughly 25% of average length of stay (1.2 of 4.2 days) which equates to 10.8 million avoidable inpatient days – that’s 29,590 full hospital beds for an entire year. The average room costs $2,873 a day. A total of $1.5 billion could be saved annually just by reducing avoidable days by 5%.

![]() By continuously evaluating the medical necessity of ongoing treatments, concurrent review minimizes delays for patients as they are already receiving care, creating more seamless transitions of care. This ensures timely access to vital treatments while still allowing payers to manage costs responsibly. While it may not directly impact the immediate cost to the patient, it streamlines the process for providers, allowing them to focus on delivering quality care.

By continuously evaluating the medical necessity of ongoing treatments, concurrent review minimizes delays for patients as they are already receiving care, creating more seamless transitions of care. This ensures timely access to vital treatments while still allowing payers to manage costs responsibly. While it may not directly impact the immediate cost to the patient, it streamlines the process for providers, allowing them to focus on delivering quality care.

- How important are more seamless transitions of care? Some studies indicate up to one-fifth of patients experience an adverse event within two weeks of hospital discharge, many of which could have been mitigated or prevented. Such adverse events could include medication errors, falls, or infections and cost anywhere from $12-44 billion a year in the U.S.

Conclusion

Concurrent review is a linchpin in the care continuum — undervalued not because it’s unimportant, but because its benefits are often behind the scenes. With rising financial pressures and increased focus on value-based care, investing in smarter, more integrated concurrent review processes is not just necessary — it’s urgent.

Building trust with technology solutions takes time, but luckily there are already proven tools in place to improve concurrent authorization, or medical necessity decision-making, processes.

Increased use of payer portals, for example, present an opportunity for increased alignment between health systems and health plans, reducing unnecessary denials. Payer portals allow hospitals to enter clinicals more efficiently, in a more timely fashion, versus faxing clinicals to a RightFax type of email inbox, where someone must then pull the fax and work the case. Increased use of payer portals would assist in more timely, efficient clinicals and lessen the administrative burden.

Better yet is the use of shared, real-time views of objective data and predictive analytics that allow for bidirectional communication – a shared framework and common language for eased negotiations back and forth. Such a framework also allows for agreed upon cases that can be automated based on historical alignment, saving time and improving focus on the most sensitive cases.

This more comprehensive way of tackling pervasive payer-provider friction and closing informational gaps to align on appropriate care paths is already saving health systems millions of dollars. Just one example of this is Beacon Health System.

Learn how Beacon Health System has saved more than $95 million by using Xsolis solutions.

Request a consultation to learn how Xsolis’ Solutions can improve efficiencies at your organization.